Pico-Pond, a networked PICO-8 demake

Earlier this week I released Pico-Pond, a networked PICO-8 demake of Frog Chorus, a web-project I love by v buckenham and Viviane Schwarz.

You can play Pico-Pond for free in your browser here: https://andymakes.itch.io/pico-pond

You can also look through the source code, which I hope will be helpful for anybody else looking to make a networked PICO-8 game. The code is commented and (hopefully) easily readable.

Please keep in mind that this was a weekend project that was never meant to scale beyond 20 players. I did not try to make it super efficient or account for every edge case.

Overview

Just like in the original, you control a single frog in a pond populated by other real people. All you can do is hold a button to grow in size and then release it to make a ribbit. The ribbit is louder and longer the bigger your frog is when you release. All credit for this design goes to buckenham and Schwarz. It is deceptively simple, but the act of communicating with strangers this way is surprisingly rich.

What makes Pico-Pond somewhat unusual for PICO-8 is that it is networked! This is not a standard feature of PICO-8, but is possible in a web build through some fairly straightforward hacks. I've been curious about exploring this for a while after reading about some early work in this direction. I selected a Frog Chorus tribute both because I loved the original and because the simplicity of it lent itself to a good first project.

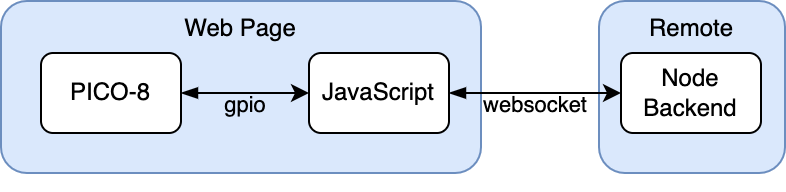

Before I get into the details, here's an overview of how this project connects multiple users into the same PICO-8 experience. The magic is in the gpio pins added in version 0.1.7. The gpio pins represent a set of 128 bytes of memory and were designed for PICO-8 projects on the raspi to allow games to be able to respond to hardware on the device. For whatever reason, they are also accessible to JavaScript running alongside the game in web builds. This can bridge communication between the PICO-8 game and the surrounding web page. Once you've broken out into JS, the sky is the limit.

This particular project uses a setup like this: The gpio pins are used to allow my JS and the PICO-8 game to communicate. My frontend JS then communicates to a node server hosted on Heroku using a websocket.

JS / PICO-8 Communication

The first time I read about doing something like this was a few years ago when I stumbled across this post by edo999. This used JavaScript equivalents of the PICO-8 peek & poke functions to insert or read values from the heap. Seemed promising and I kept it in my back pocket as something I wanted to check out. More recently I encountered seleb's post about a functional twitter client he wrote in PICO-8 (it's really cool. Check it out!). He was using the gpio method and was kind enough to include his source code.

This method is very easy! For the JS file, all you need to do is create an array of 128 elements called pico8_gpio. After exporting the PICO-8 game as a web page, the javascript file needs to be included in the HTML file. The 128 elements of this array map to 128 locations in the PICO-8 memory starting at location 0x5f80. To write to slot 2 and read from slot 5 in JavaScript I might write

pico8_gpio[2] = 32;

let my_val = pico8_gpio[5];

And to do the same in PICO-8 I would use peek & poke to manipulate memory

poke(0x5f80+2, 32)

local my_val = peek(0x5f80+5)

That's pretty much it! One tricky thing is that this only works when running a web build, so testing in the editor becomes tricky. I wound up writing some testing values to memory in _init() so that my app thought it was connected. Needing to make a web build definitely increases debug time.

Managing Communication

There are 128 gpio pins to use! As seleb notes in his post, “128 bytes is a pretty big chunk of data for a PICO-8 app.” Pico-Pond doesn't even come close to using all of them. Seleb came up with a clever structure to allow the JS and PICO-8 elements use the same pins in order to send large amount of data, with the first pin acting as a control pin letting both apps know whose turn it was. Luckily my needs were simpler so instead every pin is designated as being for a specific app. Either the JS script writes to it and PICO-8 reads, or the other way around. They never write to the same pin.

One note is that although I could store negative numbers in these addresses from PICO-8, I was not able to write a negative value from JS. So some things might seem a little odd (like using 200 to mean that a frog is not active). I'm sure this can easily be fixed, but it was never enough of an issue for this game.

Here's the breakdown of pins in the finished project. I didn't settle on 20 frogs right away and I wasn't sure how many pins I would need for each frog, so I left the first 100 pins for game-state information from the backend and started additional data at pin 100.

| PIN number | Description | Who writes to it | Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1-20 | Frog Values | JS | values of all frogs in range from 0-100. 200 means that frog is unused |

| 21-99 | unused | unused | unused |

| 100 | Player Input | PICO-8 | 1 if button held, 0 if not |

| 101 | ID | JS | ID of this player. Set by backend |

| 102 | Cart Start | PICO-8 | starts at 0, set to 1 when cart is loaded to let JS know it's ready |

| 103 | Status | JS | Tells the game the status of the connection to the backend (waiting, connected, room full, disconnected/error) |

Pin 0 wound up being unused when I moved all the frog values up by 1 pin to match PICO-8/Lua style of indexing arrays at 1 (a constant source of consternation).

The values in 1-20 and 101 get set from the backend, but not directly. The JS script communicates with the backend via the websocket. There is a regular pulse from the backend with the gamestate. When the frontend receives this message, it writes the values to those 20 pins. Likewise, when the backend responds to a new player with a frog ID, the frontend JS writes that ID to pin 101.

The JS script does not manage game logic at all. It just acts as a bridge between PICO-8 and the backend.

Keeping the Data Small

You might notice that each frog in the game is stored as a single number between 0 and 100 (with 200 meaning they are inactive). Although I didn't think I would even come close to using all 128 pins, I wanted to keep the amount of data moving from the backend as small as possible (mostly so that I could easily send the entire gamestate instead of needing to have a more clever system).

One way to approach a game like this would be to have the backend create a frog when a user connects. Things like the X and Y, the color etc of the frog could be generated and stored in the backend. This would be fine, but then all of those attributes need to be sent to clients who connect to the game. In this game the only thing that changes is the size of the frog (increasing when the button is held and then returning to 0 when released), so I wanted that to be the only value managed by the backend. I think an argument could be made for just having the backend track if a player is holding down the button or not and letting the PICO-8 game manage the rising and falling value, but I wanted the backend to have an accurate snapshot of the current gamestate so that a newly connected player would have all of the correct data.

Right now, when a new player joins, the backend finds a random open frog and sends them the ID of that frog. The frog object on the backend consists of a number value and a boolean for if the player is holding the button. Every tick (targeting 30FPS to match PICO-8) the frog value goes up if the button is held and down if it is released. Changes in the user's button state are sent via websocket whenever the frontend JS sees that the input pin has changed value.

So what happens to those other attributes? They don't really have to be consistent; they could be randomized when the game starts, but that doesn't feel right. If I'm the red frog in the bottom left corner, it feels like I should be that frog for everybody.

The easily solution here is to randomize these things, but to seed the random number generator so that the values are the same for everybody. I wrote a simple (and very inefficient (please don't @ me if you read the source code)) function to randomly distribute the positions of the frogs to roughly fill out the screen and then randomized the other frog attributes (color, sound etc). For each of these steps I tried out a few different seeds until I found ones I like. Now all instances of the game have the same pond without needing to send those extra values across the wire.

Audio

The last thing I needed to do was make the frogs ribbit. One of the charming things about Frog Chorus is that the different frogs have different voices (audio recordings of people saying “ribbit”) that get played at different speeds and volumes depending on how big the frog is when you release. The fact that the frogs sound different from each other and that the sound is modulated by how long the button was held contribute in a big way to the conversational feel of Frog Chorus. You can get into a groove with people where you do lots of little chirps or each grow really big to do a loud ribbit at the same time; it's a lot of fun! I wanted to make sure that this aspect was captured as well.

As such, one-shot sound effects were probably not going to cover it. Luckily there are some tools I know from making hyper-condensed tweet jam games that allow for some dynamic audio generation. Weirdly, the print command can be fed a special character that causes the string that follows to be played as audio. This whole portion of the PICO-8 documentation on control codes is pretty interesting.

The basic format is “\ab..e#..b” where “\a” is the control code that signals to PICO-8 to treat the string as audio and then everything after that is telling it what to play—in this case a B and E# and another B with a slight pause in between each note.

There are some additional properties available such as volume (v), instrument (i), effect (x), and speed (s).

For example let's look at “\as9v7x3i0f..d-..f”. Going from the end and working our way to the left this string plays an F note followed by D flat then another F (“f..d-..f”) using instrument 0 (“i0”), effect 3 (“x3”) at volume 7 (“v7”) and speed 9 (“s9”).

Not very pretty to look at but it gives a lot of control.

Speed and volume are fantastic for modulating the sound. I mapped the size of the frog when the button is released to these values so that big frogs play a slow, loud sound and little frogs play quick fast ones. After some trial and error, I got it so the length of the sound roughly matches the length of time it takes the frog to shrink back down to the base size.

I'm sure a sound effects person could do a better job, but I got a fairly nice ribbit-y trill by going back and forth between two notes like this: high note, low note, high note, low note. These notes are defined for each frog in the setup function using the same seeded random function as the other attributes.

Then, to give frogs their own voice, I also randomize the instruments and effects. Not all of them sound froggy, but I tried each one and made a pool of acceptable options for each frog to pull from in setup.

If there are tons of frogs in the pond, these sounds are likely to get cutoff when multiple frogs use the same instrument. I think that's OK though because that means there are enough people using it that it will feel lively anyway.

Wrap Up

There's a bit more going on, but those are the exciting parts! Please dig into the code if you're curious. Once I was finished I went over it and commented everything to try and make it as easy as possible to parse.

I hope this is helpful if you want to add a bit of networking to your own PICO-8 projects!

Credits and Links

Frog Chorus was made by v buckenham & Viviane Schwarz.

The frog pic used in the game is a lightly modified version of an image made by scofanogd and released with a CC0 license.

Thanks to Sean S. LeBlanc for the breakdown of his PICO-8 twitter client, which was a key part of getting this off the ground!

Thanks to lexaloffle for PICO-8!